Unraveling the Fear of failure : A study on the impact of atychiphobia among young mexican women in california

On mai 16, 2023 by labo recherche StandardAn article by Kenza Khamali and Sophia Kharbouch –

Questioning the myth of the American Dream so vividly anchored in California when it comes to success through employment for young women of Mexican origin.

Over the last decades, there has been considerable growth regarding research on emotions. Fear, being one of them, has always been shunned by people and seen as a matter to shy away from. The emotion of fear is a core part of a human’s experience. The subject of fear is overwhelmingly deep, which led us to think that exploring this subject from a sociological and psychological point of view would best fit our preferences. As a result, we narrowed our field by asking ourselves one question: what are the first three words that come to mind when we think about “fear”? The three words were: phobia, anxiety, and pressure. Although, deeper fears that plague a majority of the human population do not come from living organisms or materials but are well inside our brains. They are implemented by precedents or by society.

Therefore we chose to focus specifically on the fear of failure scientifically known as « atychiphobia », a fear that can significantly impact an individual’s life. It is a common concern for many people and can be particularly prevalent among women in modern society. People with this fear often avoid taking risks or trying new things because they are afraid of not succeeding. They may also be overly self-critical and have difficulty accepting failure, even when it is a normal part of the learning and growth process. According to « The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic Intervention » by Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes (1) , research has shown that women may be more likely to experience it due to societal expectations, stereotypes, as well as a lack of confidence in their abilities.

The chosen time frame for this research paper covers a period of time from the early 1900s to today as it provides a wealth of resources, offers relatable and thought-provoking content, and allows us to reflect on both positive and negative progress. That is why modern society’s relevance and interest level make it an ideal subject to study and analyze. This research paper seeks to explore the fear of failure among young Mexican women living in California and its impact on their access to a first job. California is often seen as a land of opportunity, where the American Dream of success through hard work and determination can be achieved. However, for young Mexican women, this dream may be elusive due to a range of cultural, social, and economic factors that create barriers to accessing employment opportunities. In countries such as the U.S., these issues may be compounded by the high-pressure and fast-paced culture of the region. Despite California’s well-known Democratic policies, job opportunities may not always be equally accessible to all due to the state’s high migratory flow. However, according to the governmental website Bureau of Labor Statistics (2), California’s job market has grown by 3.5% in the past year, adding over 500,000 new jobs to the economy. Our research aims at delving into the fear of failure in modern society, as experienced by first or second generation Mexican American women living in California, who are in the country legally, and focusing on how this fear affects their access to a first job. By combining sociological and psychological theories, we seek to understand the unique challenges these women face in the United States and the cultural and societal factors contributing to this issue. Our goal is to shed light on how fear of failure can act as a barrier in accessing employment opportunities and to understand the difficulties faced by a specific group of women on the job market.

Furthermore, we will examine the representation of these women in the workforce and the difficulties they face in reaching leadership positions. Key terms in this study include « fear of failure, » which refers to the anxiety or reluctance to take risks due to a fear of not succeeding, and « access to employment, » which refers to the ability of individuals to find and secure employment opportunities.

First and foremost, California, the « land of dreams, » has long been touted as a place where anyone can achieve success and prosperity through hard work and determination. However, for young Mexican American women, the reality of the California job market is far from the idyllic image portrayed in popular media. The migratory flux from Mexico to California has been a significant factor in shaping the state’s demographics and economy. According to the Migration Policy Institute (3) , California has the largest number of Mexican immigrants of any state, with approximately 4.1 million in 2019. For Mexican Americans, the state has particular significance due to its proximity to Mexico and the large Mexican American population. The migratory history and experiences of discrimination faced by this population can impact their economic opportunities and contribute to their fear of failure in the workplace. According to a report by the Pew Research Center (4) , Mexican Americans are one of the largest and fastest-growing ethnic groups in the United States, with a significant number residing in California. This trend is not new; Mexican immigration to California has been ongoing since the 19th century, with a surge in the 20th century due to the demand for agricultural labor. Despite this long history, Mexican American women specifically, continue to face challenges in accessing quality jobs and economic mobility.

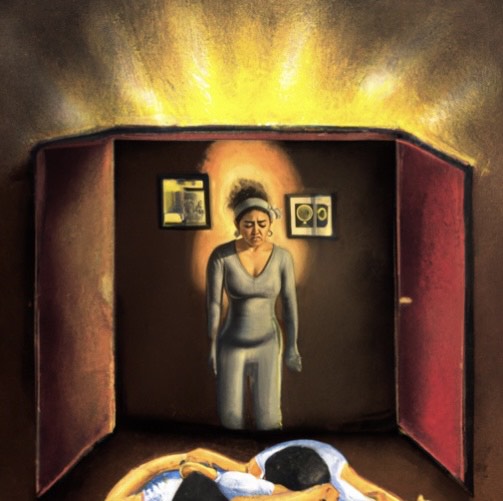

Linking the cultural pressures faced by Mexican American women in California to the larger societal norms in Mexico, a report by the Pan American Development Foundation (5) states that « women in Mexico are regularly expected to prioritize their roles as caretakers above all else and perform flawlessly in all aspects of their lives. This is not just an expectation placed on mothers, but on women in general. And when they fail to fulfill these roles flawlessly, they can feel like they are letting their families down and falling short of societal expectations. »

Indeed, women in Mexico are still expected to fulfill traditional gender roles, including domestic labor, childbearing, and caregiving for older family members. This cultural pressure found in many other countries can create a belief that any failure or mistake is a reflection of a woman’s worth as a person, leading to feelings of shame and inadequacy. The societal pressure for Mexican women to prioritize family and community welfare can contribute to their fear of failure to meet those expectations, which may impact their willingness to take risks and pursue their career goals, particularly for Mexican American women with varying levels of education. The fear of finding employment is a common concern for many individuals, but it can vary depending on the individual’s educational background. Mexican American women, in particular, may face different levels of fear based on their education level.

This first axis focuses on the difference in fear between Mexican American women with and without a college degree. Our first point being the difference in the origin of the fear contingent on the educational background of the woman. A woman with a college degree will experience a different process than a woman without a college degree or an American K-12 education as far as finding a quality employment goes. That being said, Mexican American women without a college degree may face more complex challenges in finding quality employment due to limited job opportunities, language barriers, and discrimination in the workplace. According to a report by the National Women’s Law Center (6) , in 2020, white women without a college degree had an unemployment rate of 5.2%, while Latinas without a college degree had an unemployment rate of 10.3%. Lack of education can also limit their access to well-paying jobs, causing financial strain and perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Mexican American women without a college degree face several challenges when it comes to accessing quality employment. Another study presented by the CAP 6 found that Hispanic women earn only $0.57 cents for every dollar earned by non-Hispanic white men, whereas white, non-Hispanic women, earn $0.79 highlighting the wage gap and economic inequality faced by this group.

Moreover, Language barriers can also be a significant obstacle and factor of discrimination for Mexican American women without a college degree seeking employment. According to the Migration Policy Institute (7) , nearly one-third of Mexican immigrants aged 5 and over living in the U.S. in 2019 had limited English proficiency. « This can make it challenging to navigate the job market, communicate with employers, and access training or educational opportunities”. Additionally, discrimination based on language skills can also limit job prospects and opportunities for advancement. As stated in the book « Mexican Women and the Other Side of Immigration: Engendering Transnational Ties » by Susana Delgado (8) , many Mexican women who work in the maquiladora industry in cities along the U.S.-Mexico border, such as Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, do not have a college education. The majority of these women have not completed secondary education and often come from rural areas with limited access to education. The maquiladora* industry offers low-skilled jobs, such as assembly line work, in which women are subject to poor working conditions, long hours, and low wages. As a matter of fact, low-wage jobs typically create a cycle of poverty and limit social mobility, a phenomenon known as social reproduction. However, despite the terrible conditions in the maquiladoras, some argue that working in them is still better than being a low-wage worker in the US, as the Mexican culture still holds women in higher regard. Indeed, “Mexican American women are particularly vulnerable to this cycle due to factors such as limited educational opportunities and discrimination in the workforce.” According to a report by the Economic Policy Institute (9) , nearly 57% of Mexican American women work in low-wage jobs, compared to 43% of all women in the United States.

*Maquiladoras (also known as « twin plants ») are manufacturing plants in Mexico with the parent company’s administration facility in the United States. Maquiladoras allow companies to capitalize on the less expensive labor force in Mexico and also receive the benefits of doing business in the United States.

However, it is important to note that not all women who start in low-wage jobs tend to remain in them. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (10) found that women who started in low-wage jobs had a 57% chance of escaping low-wage work after 10 years. While social reproduction is a pervasive issue, it is not inevitable, and policies that support upward mobility and access to education can make a difference. Still, the maquiladora industry is known for its high turnover rates, which can make it difficult for these women to achieve economic stability and improve their quality of life. This lack of education can limit their access to well-paying jobs and cause financial strain, perpetuating the cycle of poverty and constant fear of staying ‘stuck’ in this cycle. These women also face challenges in acquiring job-related skills and knowledge, as well as difficulty in obtaining promotions or higher-paying positions, which is near impossible in their conditions. This can result in limited opportunities for career advancement and economic stability. In her book « Made in Mexico: Regions, Nation, and the State in the Rise of Mexican Industrialism, 1920s-1940s, » author Susie Porter 11 also writes about the struggles of women working in maquiladoras in the 1980s. She notes that many women were brought in from rural areas where educational opportunities were limited, and that they had little choice but to take low-paying, unskilled jobs in the maquiladoras. On page 155 of her book, it is mentioned that “The workforce was recruited from rural areas, often from among the poorest and most marginalized segments of society. For these women, working in the maquiladoras meant exchanging one set of hardships for another. The working conditions were harsh, with long hours, low wages, and no job security. Women had to contend with discrimination based on their sex, their class, and their status as migrants. Many had children to care for and households to manage, yet they had to find ways to juggle work and family responsibilities » (12) . The precarious nature of their employment makes it difficult for these Mexican American women with majorly no education to plan for their future, which makes the whole ordeal overwhelming and paralyzing for them, contributing to their overall sense of fear of failure. While the experiences of Mexican American women working in the maquiladoras along the U.S.-Mexico border are undoubtedly relevant to the broader issue of workplace discrimination, it’s important to recognize that their situation is specific to the border region and may not be representative of Mexican American women’s experiences across California.

In addition, using recent and relevant statistics and information, we have constructed a hypothetical portrait that sheds light on the challenges faced by Mexican American women without a college degree and their relationship with the fear of failure. Meet Ana, Ana currently works as a caregiver for the elderly, earning only $12 per hour. This is one of the lowest-paying jobs in California, and even with full-time work, it’s difficult for Ana to make ends meet. In fact, according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator (14) , a single adult in Los Angeles County needs to earn at least $15.60 per hour to cover basic expenses. Let’s imagine that Ana has two children, which makes it even harder for her to make ends meet on a low wage. According to the 2019 American Community Survey (15) , the poverty rate for Hispanic households with children under 18 years old in Los Angeles County is 28.3%, compared to 10.2% for non-Hispanic white households. This shows the significant economic disadvantage faced by Hispanic families with children in the county. Moreover, the lack of access to higher education is a significant barrier for Mexican American women in California. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (16) , only 12.2% of Mexican American women in California hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 22.9% of non-Hispanic white women. This means that Mexican American women face limited opportunities for upward mobility and higher-paying jobs. The intersection of race and gender also contributes to the challenges faced by Mexican American women without a college degree. According to the same American Community Survey (15) , the median income for Hispanic women in Los Angeles County is $29,000, compared to $50,000 for non-Hispanic white men. This wage gap, coupled with the higher poverty rates for Hispanic households with children, highlights the economic disparities faced by Mexican American women in California. Given these challenges, it’s understandable that Mexican American women without a college degree in California may experience a high level of fear of failure.

With limited opportunities for upward mobility and higher-paying jobs, failure can mean losing the little they have managed to achieve so far and struggling to provide for themselves and their families.

On the other side of the coin, Mexican American women with a college degree may have greater access to resources such as career counseling, networking opportunities, and internships that can help them navigate the job market. They may also be more likely to pursue careers in higher-paying fields such as STEM, which can lead to greater financial stability and career satisfaction. A study conducted by the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (17) revealed that college majors in STEM fields lead to higher-paying careers. In 2015, Hispanic women who majored in STEM fields had median earnings of $54,000, while those who majored in non-STEM fields earned only $45,000. However, despite holding a bachelor’s degree or higher, Hispanic women still face significant wage disparities in comparison to non-Hispanic white men. According to the National Women’s Law Center (18) , Hispanic women with a college degree or higher earn only 71 cents for every dollar earned by non-Hispanic white men with the same level of education. Moreover, compared to non-Hispanic white women with similar education, Hispanic women with a college degree are less likely to hold management or professional positions. A case study found in the “The Routledge Handbook of Chicana/o Studies” edited by Cindy Cruz and Marivel T. Danielson, Routledge, 2018 19 illustrates our point perfectly. Indeed, Maria Elena Salinas is a Mexican-American American broadcast journalist, news anchor and author who was born in Los Angeles and grew up in a Spanish-speaking household. Salinas’ parents immigrated to the United States from Mexico in the 1940’s. She obtained a bachelor’s degree in Spanish and Communications from California State University, Los Angeles. As a journalist, Salinas faced numerous barriers and discrimination due to her gender and ethnicity. In the early days of her career, she struggled to find work as a female Hispanic journalist, as the industry was dominated by white males. She also faced challenges in being taken seriously as a journalist and gaining access to important sources and stories. In one interview, Salinas shared how she had to fight for her job as a news anchor at a local TV station because she was a woman and Hispanic. She had to go through numerous auditions and tests to prove herself, and even then, she was paid less than her male colleagues. Despite these challenges, Salinas persisted and eventually became a respected journalist and news anchor, winning numerous awards for her reporting. Salinas also faced discrimination and barriers when covering stories related to the Hispanic community. In the same interview, she spoke about how she faced criticism and backlash from the Hispanic community for covering stories they felt were negative or portrayed them in a bad light.

However, Salinas believed it was essential to report the truth and give a voice to all communities, even if it was difficult. In addition to these challenges, Salinas also faced language barriers early in her career, as English was not her first language. She had to work hard to improve her English skills and become proficient in both English and Spanish, which was a valuable asset in her career as a bilingual journalist. She was called the voice of Hispanic America by the New York Times, being one of the most recongnized Mexican American woman in the U.S. Maria Elena Salinas had a college education, which provided her with a certain level of confidence and preparedness for entering the workforce. However, even with her education, Salinas still faced significant barriers and fears when trying to secure her first job.

Additionally, when examining the experiences of Mexican women in the United States, it’s important to recognize the unique challenges they face in comparison to other groups. Mexican women in the U.S. are marked by specific challenges that are distinct from those encountered by white women for example. The arduous process of immigrating to the U.S.can be a daunting task for many Mexican women, and it can be compounded by their limited resources and low-income backgrounds. According to the Migration Policy Institute (20) , as of 2019, Mexican immigrants constituted 25% of the total foreign-born population in the country, with a majority of them seeking better economic opportunities. Unfortunately, the process of obtaining legal status can be difficult, stressful, and expensive, which can act as a significant barrier for many Mexican women.

In addition to the challenges related to immigration, Mexican women may face difficulties adjusting to a new culture. Learning a new language, adapting to unfamiliar social norms, and dealing with homesickness and cultural isolation are some examples of the obstacles they may encounter. As per a report by the Pew Research Center “U.S. Hispanic population has long been characterized by its diversity, September 2017” (21) , approximately 43% of Mexican immigrants say that they speak English « not at all » or « not well, » which may hinder their ability to access vital services such as healthcare and education. Furthermore, Mexican women are often concentrated – meaning they are more numerous – in certain industries, such as agriculture or domestic work, which are notoriously low-paying and lack job security. This phenomenon, known as labor market segregation, can further limit their economic mobility and restrict their job opportunities. The National Agricultural Workers Survey (22) , an ongoing study conducted by the United States Department of Labor reports that over half of all farmworkers in the U.S. are Mexican, with women comprising around one-third of this group, the latest data is from 2017. Additionally, the physically demanding nature of these industries can expose Mexican women to various health risks, including exposure to pesticides or injuries from manual labor, which can have significant long-term consequences for their physical and mental health. Which then might become bigger and heavier issues considering other barriers they carry, such as language difficulties.

In contrast, white women are more likely to work in higher-paying industries, such as finance or healthcare, which can provide greater job security and fewer health risks. Many reasons could contribute to that fact ; historically easier access to education and opportunities within their own country, bias in hiring or even promotion processes and so on. The National Women’s Law Center 23 reports that in 2019, white women in the United States had a median weekly earnings of $825, while Latinas earned only $652 per week. The poverty rate for Latinas was 21.7%, which is higher than the poverty rate for white women at 8.7%. These differences in experiences highlight the unique challenges that Mexican women face and underscore the need for targeted interventions to address the disparities and inequalities that exist within the U.S. workforce.

Exploring the issue of gender and race in the labor market – and all the precedent issues – requires a theoretical framework that considers the complex ways in which these factors intersect. In this final axis, we delve into two key theoretical frameworks – intersectionality and the glass ceiling – and examine their impact on the experiences of Mexican American women. Drawing from seminal works such as ‘The Intersection of Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the Labor Market’ by Claudia Goldin and Cecilia Rouse (24) , and ‘Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Immigrant Concentration on the Promotion Rates of Minorities’ by Fatih Guvenen and Jae Song (25) , we seek to answer how the concept of the glass ceiling affects Mexican American women differently than other women in America.

The concept of the « glass ceiling » refers to the invisible barriers that prevent certain groups of people from advancing to higher levels in their careers, particularly in leadership positions. While progress has been made in breaking down some of these barriers, the reality is that many women and other minorities continue to face obstacles in their professional lives.

Notwithstanding this concept’s intimidating nature, for Mexican American women, the glass ceiling can have an even greater impact due to the intersectionality of their identities. As noted in ‘Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Immigrant Concentration on the Promotion Rates of Minorities’ by Fatih Guvenen and Jae Song (26) , Mexican American women experience discrimination and bias based on both their gender and ethnicity. Inflated by the eventual fear of failing in such conditions, these women’s paths result in limited access to higher-paying and more prestigious job opportunities, despite their qualifications and experience. Additionally, « Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Immigrant Concentration on the Promotion Rates of Minorities » by Fatih Guvenen (27) and Jae Songieve highlights the impact of immigrant concentration on the promotion rates of minorities, including Mexican American women. The study found that when there are high concentrations of immigrants in a workplace, the promotion rates of minorities can be negatively affected. Guvenen and Song state, « Our results suggest that high concentration of immigrants within the firm can hinder the promotion of minority workers, particularly those who are less integrated into mainstream society ». These theoretical frameworks are important in understanding the challenges that Mexican American women face in breaking through the glass ceiling. While progress has been made on a global level, the reality is that there is still work to be done in addressing the unique obstacles faced by this group. All taken into account, these elements make failing a wider issue for these women. Obliquely, intersectionality is a crucial factor to consider when discussing the challenges faced by Mexican American women in their professional lives since as mentionned previously, they experience discrimination and bias based on both their gender and ethnicity. Mexican women who do pursue careers may be viewed as « unfeminine » or « selfish, » which can further exacerbate their fears of failure and alienation to meet certain goals or objectives.

Furthermore, Mexican women who are also members of other marginalized groups, such as LGBTQ+ individuals or individuals with disabilities, may face even greater challenges in the workplace. They may experience intersectional discrimination, where their various identities intersect to create unique forms of oppression and discrimination. The intersection of these identities creates a more complex and challenging experience, escalating their anxiety and fears associated with failing. Moreover, the concentration of immigrants in the workplace, as highlighted by Guvenen and Song, adds another layer to the issue. The barriers that Mexican American women face in breaking through the glass ceiling are not just limited to individual biases or lack of opportunities, but are also affected by systemic factors. The systemic factors that contribute to these challenges are numerous, including but not limited to, institutionalized racism, gender inequality, lack of access to education and resources, and exclusionary workplace policies. Therefore, acknowledging and addressing these factors is crucial to creating a more equitable and inclusive professional environment.

Therefore, fear of failure differs depending on one’s educational attainment and socioeconomic status. Mexican American women with and without college degrees face different challenges when it comes to their fear of failure. Women without a college degree may face limited job opportunities, language barriers, and discrimination in the workplace, which can cause financial strain and perpetuate the cycle of poverty. Lack of education can limit their access to well-paying jobs, creating a constant fear of staying ‘stuck’ in this cycle.

Furthermore, they may have difficulty in obtaining promotions or higher-paying positions, which can result in limited opportunities for career advancement and economic stability. On the other hand, Mexican American women with a college degree will experience a different process when it comes to finding quality employment. While they may have better job opportunities and higher earning potential, they may also feel pressure to perform at a high level and live up to their potential. They may have invested significant time and money in their education, which can create a fear of not being able to repay student loans or live up to family and societal expectations. Additionally, they may experience discrimination and biases in the workplace due to their gender and ethnicity.

Despite these differences, Mexican American women with and without college degrees share similar fears of failure. Both groups may struggle with self-doubt, imposter syndrome (in which a person doubts their skills, talents, or accomplishments and has a persistent fear of being exposed as a « fraud”) and a constant fear of not living up to expectations. They may also feel pressure to support their families and communities, which can create additional stress and anxiety. This fear can be particularly strong in our demographic group, since most of these women feel like they have a lot to lose if they fail or do not meet their own or others’ expectations. Furthermore, both groups may face societal and cultural expectations that can create a fear of not meeting traditional gender roles or cultural norms.

Gloria Anzaldúa (1942-2004) (28) ; American author, scholar of feminist theory, and queer theory once said « Being a Chicana writer means having a deep knowledge of our cultural heritage and history, the experiences of our mothers and abuelas, and the struggles and hardships that we face as women of color in this society. It means facing the fear of failure and rejection, but persevering nonetheless in order to tell our stories and create change ».

The American Dream promises success through hard work and determination, yet for young Mexican American women in California, that promise often remains unfulfilled. In the shadows of the Golden State’s bustling metropolises and Silicon Valley’s tech giants lies a harsh reality of poverty, discrimination, and limited opportunities. These women must navigate the minefield of cultural expectations, gender norms, and systemic barriers, all while grappling with a pervasive fear of failure that threatens to stifle their dreams before they even begin. While some may find a path to success, many more are left behind, held back by a society that fails to recognize their potential and barriers that keep them in low-wage jobs and perpetuate cycles of poverty.

To put it in a nutshell, the fear of failure among young Mexican women in California is a complex and multifaceted issue that requires a nuanced understanding of the cultural, social, and familial factors at play. As we explored the experiences of young Mexican American women in California, it became increasingly clear that the obstacles they face are not isolated incidents, but rather part of a larger systemic issue. These women confront a society that fails to recognize their potential, and a culture that places expectations and norms on them that can be limiting and restrictive. From a young age, they are pushed into taking into consideration their socio-economic background, and that they are unlikely to succeed. This constant messaging can create a sense of internalized doubt and fear of failure that permeates every aspect of these women’s lives. In the workforce, this fear can be particularly debilitating, as it can prevent them from taking risks or pursuing opportunities that might lead to greater success. This fear is not unfounded, as systemic barriers often prevent these women from accessing the same opportunities as their white counterparts, including access to education, mentorship, and networks that can be crucial for professional advancement.

Despite these challenges, many young Mexican American women in California refuse to let fear hold them back. They demonstrate resilience and determination, working hard to overcome the odds and pursue their dreams. But their efforts can only go so far if society fails to recognize and address the barriers that hold them back.

In order to create a more equitable and inclusive society, we must question the myth of the American Dream and acknowledge the systemic issues that perpetuate cycles of poverty and discrimination. We must actively work towards creating opportunities for young women of color, providing them with the resources and support they need to succeed. To address the systemic challenges facing young Mexican American women in California, there are organizations that provide support and resources specifically tailored to their needs. For example, MANA de San Diego offers a range of programs to empower Latinas through education, leadership development, and community service. The organization was founded in 1981 and has since provided scholarships, mentorship, and leadership training to Latinas in

the San Diego area. In 2020, MANA de San Diego launched the COVID-19 Latina Emergency Response Fund to provide financial assistance to Latinas and their families who were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. The Latina Center for Leadership Development focuses on political and civic engagement for Latinas, offering training in areas like public speaking and community organizing. The organization was founded in 2012 and has since trained hundreds of Latinas to become effective advocates for their communities.

The Mexican American Opportunity Foundation provides job training programs and support for low-income families. The foundation was established in 1963 and has since provided resources like ESL classes, job placement services, and parenting classes to Latinx communities in California. Their Women’s Wellness program was launched in 2017 and provides health education and services to women and girls, including mental health support and workshops on nutrition and physical activity. Additionally, Chicas Latinas de Sacramento offers mentorship, leadership development, and community service opportunities for Latinas in the Sacramento area. The organization was founded in 2009 and has since engaged hundreds of Latinas in service projects like park cleanups and food drives, while also providing mentorship and professional development opportunities. By providing these resources and support, these organizations are helping young Mexican American women overcome the barriers and challenges they face. However, more work is needed to dismantle the systemic issues that perpetuate cycles of poverty and discrimination. Only by acknowledging and addressing these challenges can we create a future where all young women, regardless of their cultural or ethnic background, have equal opportunities to succeed and thrive.

SOURCES

● « The Imposter Phenomenon in High Achieving Women: Dynamics and Therapeutic

Intervention » by Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes, published in the International

Journal of Women’s Studies in 1978 (1)

● Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers from 2022 (2)

● Migration Policy Institute (3)

● Pew Research Center (4)

● Pan-American Development Foundation (5)

● CAP, The wage gap is much wider for most women of color, Comparing 2020 median

earnings of full-time, year-round workers by race/ethnicity and sex by Robin Bleiweis,

Jocelyn Frye, Rose Khattar (6)

● Migration Policy Institute (7)

● « Mexican Women and the Other Side of Immigration: Engendering Transnational Ties »

by Susana Delgado (8)

● Economic Policy Institute (9)

● Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (10)

● « Made in Mexico: Regions, Nation, and the State in the Rise of Mexican Industrialism,

1920s-1940s, » author Susie Porter (11-12)

● MIT Living Wage Calculator (14)

● 2019 American Community Survey (15)

● U.S Census Bureau (16)

● Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (17)

● National Women’s Law Center (18)

● “The Routledge Handbook of Chicana/o Studies” edited by Cindy Cruz and Marivel T.

Danielson, Routledge, 2018 (19)

● Migration Policy Institute (20)

● Pew Research Center (21)

● National Agricultural Workers Survey (22)

● National Women’s Law Center (23)

● ‘The Intersection of Race, Ethnicity, and Gender in the Labor Market” by Claudia Goldin

and Cecilia Rouse (24)

● ‘Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Immigrant Concentration on the Promotion

Rates of Minorities’ by Fatih Guvenen and Jae Song (25-26)

● « Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Immigrant Concentration on the Promotion

Rates of Minorities » by Fatih Guvenen (27)

● Gloria Anzaldúa is an American Author, scholar of feminist theory, and queer theory.

(28)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

● « Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza » by Gloria Anzaldúa

● « The Devil’s Highway: A True Story » by Luis Alberto Urrea

● « The Maquiladora Reader: Cross-Border Organizing Since NAFTA » edited by Jessica

Livingston and Andrew Grant Wood

● « The Chicana Feminist » by Gloria Anzaldúa

● « Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples » by Linda Tuhiwai

Smith

● « The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America »

by Richard Rothstein

● « The Immigrant Paradox in Children and Adolescents: Is Becoming American a

Developmental Risk? » by Carola Suárez-Orozco and Marcelo Suárez-Orozco

● Pew Research Center – A nonpartisan think tank that conducts research on a wide

range of topics, including social and demographic trends.

● National Women’s Law Center – A nonprofit organization that advocates for policies

and laws that advance the rights of women and girls in the United States.

● « The Mexican American Woman » by María Cristina Morales

● « Barriers and Facilitators to Employment for Latina Immigrants in California, » by Olivia

Rodriguez, Marlene Berges, and Silvia M. Chavez (Journal of Immigrant and Minority

Health, 2015)

● « Fear of failure, achievement goals, and performance: A meta-analysis, » by Andrew J.

Elliot and Marcy A. Church (Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1997)

● « Barriers to Employment and Economic Security for Low-Income Latinas in California, »

by Monique W. Morris and Denise Dresser (Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor

Law, 2002)

● « Women in the Maquiladoras: Exploring the Factors that Shape Their Lives, » by Denise

Benavides and Marisol Rivera-Planter (Latin American Perspectives, 2006)

● « Breaking the Cycle of Poverty: The Role of Female Empowerment, Education, and

Employment in the Economic Growth of Latin America and the Caribbean, » by Nergis

Canefe and Bilge Erten (Feminist Economics, 2014)

● « The Effects of Discrimination on Mexican American Women’s Employment, » by M.

Anne Visser, Luis H. Zayas, and Maritza L. Salazar (Journal of Social Issues, 2010)

● « Latina Women in the California Labor Force: A Status Report, » by Yvette Lapayese and

Gayle Gonzales (Chicana/Latina Studies, 2007)

● « Confronting the Challenge of Gender Equity in the Workforce, » by Sylvia Ann Hewlett,

Laura Sherbin, and Peggy Shiller (Harvard Business Review, 2017)

● « Mexican-American Women in the Labor Force: An Analysis of Occupational

Segregation, Earnings, and Education, » by C. Matthew Snipp (The Journal of Human

Resources, 1980)

● « Latinas’ Meanings of Success: Exploring the Intersection of Gender, Ethnicity, and

Class, » by Lilia D. Monzó and Dolores Delgado Bernal (Race, Gender & Class, 2005)

Laisser un commentaire