Effective Altruism: Is It Truly The Ultimate Form Of Philanthropy?

On mai 11, 2025 by labo recherche StandardAbstract:

This paper explores Effective Altruism (EA) as a rational and efficient response to the often unreliable landscape of 21st-century philanthropy. Thus, I argue that its apparent strengths must be measured against its philosophical, moral, and political limitations. To develop this analysis, I consulted foundational texts in political philosophy and reviewed critiques of modern philanthropy. I also conducted a case study of the organization Giving What We Can to evaluate both its strengths and its areas for improvement. Additionally, by analyzing the core principles of EA, I assess whether the movement truly overcomes the criticisms leveled at conventional foundations or whether it reproduces some of the same structural problems.

Keywords: Effective altruism, philanthropy, Giving What We Can (GWWC), paternalism, longtermism.

Introduction:

As Rob Reich has observed, the role of foundations has expanded over time 1 . This is due both to the sheer number of foundations created since the twentieth century and to the existence of “unprecedentedly large foundations like the Gates Foundation.”2 As of 2014, the number of foundations had reached nearly one hundred thousand, with a total capitalization exceeding $800 billion 3 .

This is particularly striking given that the foundation as we know it today, a tax-subsidized organization that provides grants, only emerged in the twentieth century 4. Reich highlights that, despite being widely accepted and supported by the state through tax benefits, foundations were once a point of contention in American society 5. They were seen as an immediate threat to democracy for reasons that, while still relevant, have since become less visible, because of a lack of media coverage and resistance from the State6 .

In the early twentieth century, John D. Rockefeller, the wealthiest man in America then, whose fortune stemmed from the oil industry, sought to establish a “general-purpose philanthropic foundation whose mission would be nothing less, and nothing more specific, than to benefit humankind” 7 . His determination came in part from the overwhelming number of letters he received from people asking him to donate. The only thing left to do, then, was to receive congressional approval.

However, opposition to a large organization capable of mass donations was significant. Rockefeller spent years lobbying Congress because he had underestimated the senator’s reluctance to approve his groundbreaking foundation 8. The general public’s attitude reflected the Congress’s opposition as well: “For many Americans, foundations were troubling not because they represented the wealth, possibly ill-gotten, of Gilded Age robber barons” 9 . Therefore, the issue was that such institutions were perceived as having the potential to supplant the state. A foundation with vast resources and influence could wield disproportionate power to enforce social change, implementing measures that rivaled public policy. This raised concerns that the opinions of the wealthy would take precedence over those of the majority, undermining democracy.

Additionally, the perpetual existence of foundations was seen as dangerous, as it could allow them to accumulate power with no restriction. Their private nature made them unaccountable, which, given their prominence, was seen as deeply undemocratic, as Reich explains:

“They [foundations] were troubling because they were considered a deeply and fundamentally antidemocratic institution, an entity that would undermine political equality, convert private wealth into the donor’s preferred public policies, could exist in perpetuity, and be unaccountable except to a handpicked assemblage of trustees”10 .

Despite strong opposition, Rockefeller firmly believed in the legitimacy of his philanthropic endeavor. To address congressional concerns, he proposed a series of amendments 11 to his endeavor.

– A cap on the Rockefeller Foundation’s assets at $100 million to limit its influence.

– A requirement to spend down its entire principal within fifty years to prevent perpetual operation.

– A governance structure subject to veto by a congressionally appointed board, including prominent political figures such as the president of the Senate and the president of the United States.

These amendments aimed to reassure Congress that the foundation would not constitute a democratic threat. Nevertheless, the Senate ultimately rejected the proposal. In the end, Rockefeller bypassed Congress by going through the more flexible New York State legislature12. There he presented his initial project, free of all the amendments that made the foundation almost harmless to democracy. His foundation was officially chartered in 1913 and is representative of today’s foundations, minus state subsidies.

Reich interprets these events as an example of congressional clumsiness and stubbornness13 . He suggests that the amendments proposed by Rockefeller to make his foundation accountable, would have addressed many of the criticisms that he levels at foundations today. Instead, foundations proliferated unchecked, and they are now widely praised for promoting “equality” in various sectors, despite their lack of transparency and unclear methods for achieving their stated goals, whether they’re linked to alleviating poverty or ensuring access to education for all, for instance14 .

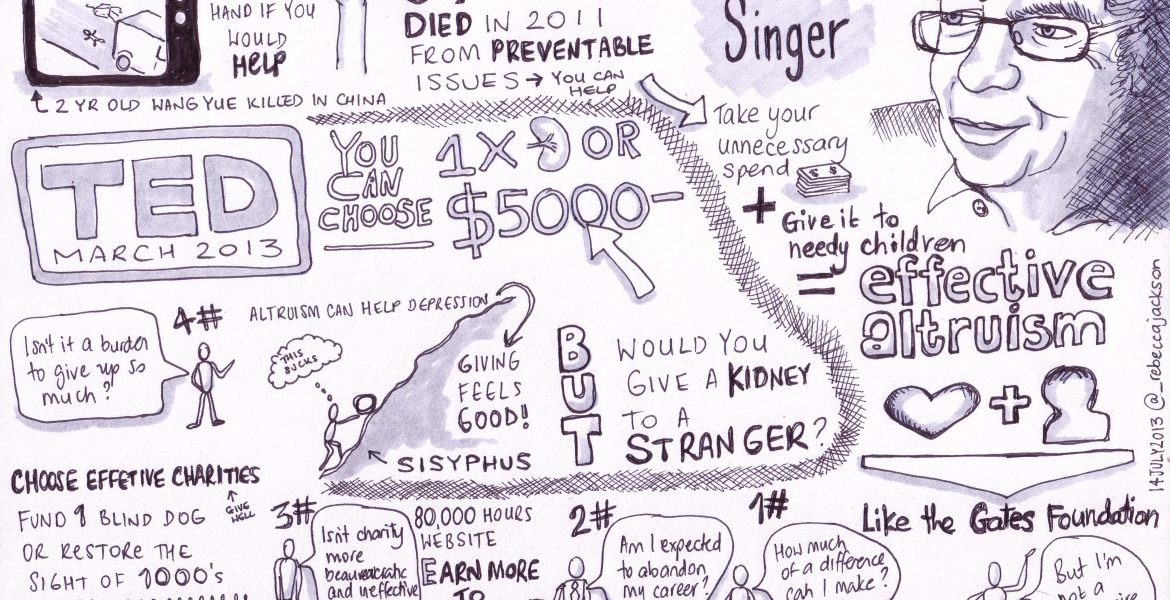

As foundations evolved, a philosophical movement emerged, shaped by the struggle for equality and the pursuit of global betterment. Influenced by utilitarianism, particularly John Stuart Mill’s ideas, the philosopher Peter Singer and other founders of effective altruism sought to determine how individuals would most efficiently improve the world. This movement crystallized between 2009 and 2012 with the creation of multiple central institutions, the word effective altruism being chosen in 201115 . They concluded that maximizing global happiness required strategic donations16. Unlike traditional charity, which often relies on emotional stimulation17 . Since utilitarianism is a form of consequentialism, effective altruism values above all the consequences of donations. Meaning, that a donor who believes in effective altruism will make sure that their donation has the maximum good impact that it could possibly have18 . Here, it is critical that the foundation itself is efficient in achieving whichever goal it chooses. So, effective altruism may appear to be the most effective and ethical form of philanthropy.

However, one might question to what extent effective altruism is the best way to approach philanthropy. Does the efficiency of a foundation make it invulnerable to all criticism surrounding democratic accountability, transparency, and power?

In this research paper, I will explore the assumption that effective altruism is the optimal form of philanthropy. In other words, how effective altruism counters some of the common criticisms leveled at foundations. I will then examine how the shortcomings of foundations such as their lack of transparency, democratic accountability, and potential to exert disproportionate influence are also reflected in effective altruism, given that large-scale foundations are central to accomplishing its goals.

I. How effective altruism avoids the criticism surrounding efficiency and transparency.

- Criticism of philanthropic foundations

Rob Reich’s recent criticism of philanthropic foundations is due to both the fact that the nobility of philanthropic endeavors is tainted by other goals, and fails to uphold the value of equality that it aims to, and to the fact that unlike during Rockefeller’s time, foundations and donations are subject to tax subsidy.19

A tax subsidy that is not linked to the cause supported, rather to the financial situation of the donor and the size of the donation20 . This apparent support of the state in whichever cause the foundation claims to ameliorate, is a neglectful policy.

This neglectful policy surrounding foundations, takes the form of, besides tax subsidy, lax access to the 501(c)(3) status, which is the legal designation that makes an organization tax-exempt and allows donors to claim deductions.21

Indeed, the criteria for qualifying as a 501(c)(3) foundation are broad enough that a vast range of organizations, regardless of their actual effectiveness or social contribution, are swept under this category22.

This unrestricted approach to the flourishing of foundations raises the issues of legitimacy according to Reich23 . If the liberty of donating is incentivized by the State, foundations do not fully belong to their donor. But to the whole community, through what Reich calls lost tax revenue24 : creating a foundation leads to the deduction of taxes. The difference between the amount of taxes effectively collected by the state, and the amount that would have been collected if the donation was not made, or if the foundation had not been created, is referred to as lost tax revenue. This is a crucial point in understanding why foundations affect everyone: the lost tax revenue would have been used to create roads, or public schools, and anything that benefits American society as a whole 25. Therefore, a deduction causes the budget dedicated to addressing these public issues to decrease, and the lost tax revenue is then redirected at the foundation, whose goal may be exclusionary by nature. For instance, creating a charity for a university is equivalent to taking the money that would have improved public services, and pouring it into a university that not all Americans will attend26 . “So foundations do not simply express the individual liberty of wealthy people. Citizens pay, in lost tax revenue, for foundations, and, by extension, for giving public expression to the preferences of rich people.”27 Here we can see the necessity of justifying that loss of tax revenue by the foundation’s aim.

Furthermore, the structure of foundations shields them from both market forces and democratic accountability28 . Unlike businesses, they don’t need to satisfy consumers. Unlike public institutions, they don’t answer to voters. In this way, foundations only exist and conform to the decisions made by a selected number of trustees that follow the donor’s intent, meaning the wish of the founder. These decisions are and should be made with the targeted population in mind, but verifying that is quite hard.

In the end, the decision of the trustees remains sovereign due to a lack of public governance. « If citizens do not like the grantmaking decisions of a foundation, there is no recourse because there is nothing to buy and no investors to hold the foundation accountable. »29

This unaccountability makes foundations all the more prominent, especially in the face of the population that it claims to help. This type of hierarchy hinders the targeted population from giving honest feedback, which is counterproductive to the foundation’s goals. As explains Reich, the targeted population often takes the role of solicitors, begging the foundations for funds. “As a general matter, people who interact with foundations are deferential and solicitous, pleading for a grant or seeking the next grant.”30

This unaccountability becomes especially problematic when paired with the fact that many foundations are designed to exist in perpetuity31 . Reich, following a line of critique that goes back to John Stuart Mill, argues that allowing the dead to bind the living through donor stipulations is deeply anti-democratic32 . No individual, no matter how wise, can predict the future’s moral priorities or social needs. Echoing Turgot’s thought, Reich agrees that “public utility is the supreme law » 33. Yet many foundations are structurally bound to uphold the original donor’s intent, even if that intent grows outdated or irrelevant. The permanence of today’s foundations may act as shackles that hinder society from progress34 .

Lastly, foundations can be vehicles for vanity, a way for the ultra-rich to secure legacy, status, or even personal gratification under the guise of generosity35 . Others use them as tax shelters, strategically donating to reduce their taxable income while maintaining control over their wealth36 . And perhaps most concerning, foundations can become mechanisms of soft power, allowing the preferences of the wealthy to shape society without public consent. This last one is a byproduct of the unaccountability that has already been mentioned. In this light, Reich sees philanthropy not as an unquestionable good, but as a potential subversion of democracy itself37 . It operates with public subsidies but without public deliberation, redistributes money without redistribution of power.

Reich emphasizes his critique by presenting the following observation: in recent decades, the number of foundations has soared, particularly those with assets under $1 million from 1993 to 201338 . And yet, civic engagement has not followed : participation in democratic institutions is stagnant or declining and volunteering rates are dropping. If foundations are meant to strengthen civil society, the current state begs the question: why do they so often fail to deliver?39

This contradiction between the noble promise of philanthropy and its structural flaws is what fuels Reich’s demand for reform40 .

To improve the current scene, other nonprofits (like Giving What We Can, Give Well…) have taken upon themselves to research the foundations’ landscape to find the best performing ones, and separate them from the illegitimate ones. These foundations are not focused on bettering the structure of foundations, rather, they focus on sorting them, and shedding light on the ones whose actions seem to align with the common view that philanthropy is meant to alleviate inequality.

It is precisely here that effective altruism enters the stage not just as a moral philosophy, but as a meta-charity and a potential solution to the crisis of philanthropy. And nowhere is this clearer than in the work of meta charities like Giving What We Can (GWWC).

Effective altruism in its principles, positions itself directly in opposition to superfluous donations41 . While Reich talks about foundations that are vanity projects, or simple tax shelters, the founders of effective altruism have worked together to create multiple meta charities42 .

The goal of meta charities is to measure the effectiveness of charities, and to recommend and inform the donation of donors. Meta Charities like Giving What We Can43 also aim to prove that giving is more effective when rigor and thoroughness are valued instead of emotional affect. Indeed on their website, pictures of children from the global south getting vaccines are rare and only specific to certain foundations they endorse like the Against Malaria Foundation 44 .

Meta Charities themselves rely on donations, for instance most meta charities receive donations from the Effective Altruism funds which support meta charities like45 :

– 80,000 hours ( 2011 by William MacAskill and Benjamin Todd a meta charity that guides young effective altruists in their search for a lucrative job, that would help them acquire a sizable salary, from which they could donate a large amount).

– Give well ( 2007 meta charity that conducts research into charity effectiveness)

– Giving What We Can

In this research paper, the third one: Giving What We Can will be presented more thoroughly because it has numerous characteristics that sets it apart from the others as a meta charity seeking to promote effective altruism, and to influence the choice of donors. Therefore it will provide us with the necessary arguments to see how effective altruism can act as a savior, when navigating the current almost saturated charity scene.

- Giving What We Can (GWWC): a solution to the crisis of philanthropy

- Presentation of Giving What We Can (GWWC)

Giving what we can was created by William MacAskill and Toby Ord in 2009, while they were still students at Oxford46 . Their meta-charity had many goals:

Firstly, like all meta charities it aimed to channel money into a body of charities which they recommend, that are effective enough, thus worthy of the money of the donors47 . For instance, by giving visibility to certain charities that are efficient but not popular, the meta charity helps the charity to reach its goal. Thereby creating more utility – “utility”, from the utilitarian philosophical point of view, being a synonym of happiness or satisfaction48 .

The charities recommended are not only chosen because of their effectiveness at achieving whichever goal they chose: they are also promoted based on the goal chosen.

This principle is based on a hierarchy of causes that effective altruism built to ensure efficiency and moral soundness49 .

Peter Singer presents a thought-experiment50 , where we have to choose between donating $100,000 as a part of the fund for the construction of a museum’s new wing or donating the same amount of money as a way to fund the restoration of one thousand blind poor people in developing countries. Here, the moral choice to make is self-evident. However, at a much smaller scale, foundations often decide to orient themselves in inessential causes or less urgent ones. In this sense, ending poverty seems like one of the most, if not the most urgent cause. In Just Giving by Reich51 , we learn that in 2005, out of the total of donations which amounted to $252.55 billion, 69% went to non-poor giving. The largest recipient being religion, (not counting religious benevolences to help the poor, rather donations for the upkeep of the facilities). Therefore, around one third of all donations goes to assist the poor52. This is according to effective altruism a misuse of resources, Peter Singer supports this claim, by referencing the work of the philosopher Thomas Scanlon53 .

« When we are faced with the needs of those who are, in Scanlon’s words, “severely burdened,” the sum of the smaller pleasures of the many have no “justificatory weight. »54 . Here the pleasures may come from donating to religion, museums, art installations and other endeavors that do not tackle pressing issues.

As such, Giving What We Can has what it calls « 3 cause areas : global health and wellbeing, animal welfare and reducing global catastrophic risk. « 55

These three causes are addressed often separately by each of the foundations recommended.

Besides the ranking, Giving What We Can( GWWC) offers other ways to donate. In case of indecisiveness, the person may donate to « Giving What We Can funds » 56 , an option that allows giving to one of the three cause areas. The money is then pooled and distributed or given to one or many of the charities that work in the cause area chosen. Similarly, the person can choose an « All Causes Bundle » 57 where the money randomly goes to fund projects that remedy the situation in one or more of the three cause areas. This flexibility can act as an incentive to donate.

Further, the apparent transparency aligns with effective altruism. Indeed, in addition to graphs, online users may access the » Impact Evolution 2020-2022″ table sheet 58 . This tablesheet presents the amount of money donated to around 20 of their major charities. It shows the effectiveness of charities based on their rankings and shows the money allocated in the span of two years for each of their cause areas. For instance, 65% of the giving was directed at improving human well being, 7% to improving animal welfare and 11% to creating a better future from 2020 to 2022 59 .

Secondly, Giving What We Can aims to promote effective altruism. This is why, unlike other meta charities like Givewell, no picture of people of the global south receiving aid that could appeal to our compassion is visible. This is not to say that effective altruism is a cold way of giving. Peter Singer, one of its main proponents, states that to be truly efficient, effective altruism needs the emotional investment of the individual60 . In other words, effective altruists have to believe that what they are doing is right, and have to be enthusiastic about it. The most efficient type of effective altruism is when that conviction and the actions undertaken in alignment with it are marked in time, and durable. Therefore, effective altruism has to be a source of happiness in the person’s life. As Peter Singer wrote, “We don’t need people making sacrifices that leave them drained and miserable. We need people who can walk cheerfully over the world, or at least do their damnedest. » 61

Therefore, the lack of emotional stimulants on their website is due to the fact that people who follow the principles of effective altruism are not truly moved by them, their conviction that giving in the most effective way is the best way to help, is enough to motivate them. So, what is abundant on their website are graphs, and a calculator that estimates how much good you can do (in terms of sending vitamin supplements to children, of lives saved, and of children treated with medicine for malaria)62 .

This calculator aims to push the user to look into how to donate effectively. It is also a reference to a unique aspect of Giving What We Can which is, the pledge.

The pledge is the cornerstone of effective altruism63 : since the beginning of the movement, effective altruists have been living modestly in order to allow 10% and more of their salary to be donated to causes. Therefore to preserve the aspect of self-restraint for the common good, that is specific to effective altruism, a user can sign the electronic pledge to give 10% or a higher percentage of their income until the day they retire64 . This pledge is not legally binding, but a token of a user’s determination to do the most good. It has now (in may 2025) 9759 people who have pledged to give 10>= of their income on a monthly basis65 .

- How does it steer clear of the flaws of the charity-landscape ?

As previously mentioned, the meta-charity Giving What We Can manages to avoid channeling money to ineffective foundations, firstly by considering the goals of the charity66.

Then, and this is what they pride themselves on, they evaluate the charities that claim to work on these cause areas (global health and wellbeing, animal welfare and reducing global catastrophic risk) through evaluators that they’ve chosen67.

Since the beginning of this enterprise, this meta charity has relied on third-party evaluators on each of the fields. Before 2023, the evaluations were conducted by the Giving What We Can team68. The team then relied on choosing an evaluator on factors like public reputation and alignment of their approach with the donor’s goals. Since then, however, they have changed their approach and choose their evaluator based on their works69 .

Their current evaluators remain strongly attached to effective altruism. This is probably due to the fact that evaluators in line with effective altruism give more weight to effectiveness, than others70 :

– ACE’s Movement Grants

– EA(Effective Altruism) Funds’ Animal Welfare Fund

– EA(Effective Altruism) Fund’s Long-Term Future Fund

– GiveWell

– Longview’s Emerging Challenges Fund

The relationship between evaluators and the metacharities website, as described on their website, is one of cooperation rather than employer to employee71 .

Indeed, the meta charity gives feedback to the evaluators to help them produce their best work. In the future, we may speculate that this type of cooperation will help sort out the scene, and denounce the ineffective foundations that waste lost tax revenue.

- Recognized Limitations and Self-Critique

GWWC acknowledges that some promising cause areas , such as climate change, remain underexplored, not necessarily due to their lack of importance, but because current organizations in those fields may not yet meet the high standards of cost-effectiveness required to displace other recommended causes 72 .

Moreover, the quality of GWWC’s recommendations is only as strong as the evaluators they rely on. For instance, they admit that while global health evaluations tend to be robust, animal welfare recommendations are still evolving and may lack the same depth of analysis73 .

They also admit past mistakes, a proof of transparency, that counters Reich’s criticism of unaccountable foundations. Between 2016 and 2020, GWWC significantly overestimated the number of recurring donations they had helped generate. The discrepancy amounted to $96 million between reported and actual donations74 . In response, they implemented alert systems for large pledges to ensure accuracy. This goes to show their commitment to improving themselves. Another concern is the potential for conflicts of interest between evaluators and the broader effective altruism movement. These conflicts of interest, while mentioned, are not explained on the meta charities website75 .

In light of this, the way that Meta Charities that avoid entertaining the foundations of Reich critics lies in plain sight: the rigor, thoroughness and transparency of Giving what we can, makes them almost impermeable to Reich’s critique.

II. The flaws of effective altruism

We have now established that effective altruism, through meta-charities like Giving What We Can, can overcome the flaws of traditional giving and normal foundations. Now, we’ll focus on the flaws of effective altruism, which have been uncovered through different lenses: political, moral, philosophical, and psychological. I’ve gathered four of them: paternalism, disregard for relational ethics, confusion and contradictions within the EA community, and lastly contradictions in longtermism.

1. Paternalism

According to Emma Saunders-Hastings, effective altruism doesn’t overcome the flaw to which almost all types of giving tend to indulge in: paternalism76.

She defines paternalism as such:

“Paternalism involves not only judgments about an agent’s absolute incompetence, which represent an affront to autonomy; it also involves judgments about an agent’s incompetence relative to the paternalist and so represents an affront to equality.”77

Effective altruism, being so preoccupied with the effectiveness of donations, treats recipients as less capable of sound judgment and agency78.

Of course, there are meta-charities aligned with effective altruism that go against this tendency. For instance, GiveWell supports GiveDirectly79 (a foundation that gives cash transfers to poor people in the global South). This way of donating is fundamentally anti-paternalistic because the recipients decide how to use the money, not the donors80.

However, this enterprise is not supported by one of the proponents of effective altruism, MacAskill , who happens to be the founder of Giving What We Can, a major meta-charity.

Indeed, Giving What We Can does not recommend them because MacAskill thinks that cash transfers are « suboptimal » due to uncertainty about spending, but that uncertainty reflects recipients’ autonomy81 .

This difference could be attributed to the fact that GiveWell is focused on research on ways of giving 82, while Giving What We Can focuses on recommending charities83 . Thus, it could be said that since effective altruism aims for effectiveness, it tends to neglect the morals surrounding how the help is given, which, from a non-utilitarian perspective, constitutes a deep failure of effective altruism that resonates with the limits of foundations, especially surrounding international giving84 . Indeed, allowing people to be part of the decisions that better their situation is beneficial long-term. Whereas hindering their participation to create faster or better results might be morally bad, according to the same logic. (Although there is no consensus or data proving that recipient inclusion improves outcomes85, theorists like Emma Saunders-Hastings emphasize the importance of respect in philanthropic practices. This argument draws on political philosophy and values like autonomy, equality and justice)86

So, Saunders-Hastings argues EA fails to give independent value to recipients’ own decision-making.

On a related note:

Some might say that if we take Saunders-Hastings’ definition of paternalism at face value, we realize that every good deed in international giving is an act of paternalism, because it seems like the donors are holding power over the recipient simply due to their respective positions87. However, to avoid any confusion, Saunders-Hastings presents one important nuance: if the product that the donor gives to the recipient is inaccessible on the market, then it’s not paternalistic to offer them useful equipment they could not access88. Therefore, giving mosquito nets in regions where malaria is present is not paternalistic. However, if the product is available on the market, such as food, water, or plaques for a roof, then the donor ought to help the recipient only through the form of money or cash transfers, with which the recipient will decide what to do89. While this definition can be contradicted if the choice of one recipient implicates children, irresponsible adults, or other dependent individuals, it still provides us with a somewhat stable groundwork to decipher between paternalistic giving and anti-paternalistic giving90.

2. Disregard for relational ethics

Saunders-Hastings also draws attention to a deeper issue: the ethical obligations that emerge from human relationships which effective altruism often neglects91. So, while paternalism highlights a failure to respect recipients’ autonomy in decision-making, the disregard for relational ethics is proof of a lack of adherence to moral expectations92 . This point is based on a non-utilitarian perspective, meaning a view of actions that doesn’t favor the consequences or ends over the means. It’s interesting to mention, since it allows us to see how effective altruism is viewed by opposing philosophical movements93 . Emma Saunders-Hastings asserts that EA focuses on outcomes (how much good is done), ignoring how the help is delivered. In other words, it overlooks relational wrongs like paternalistic disrespect and lack of reciprocity94.

To exemplify her point95, she mentions an anecdote involving MacAskill and potential recipients of a foundation: MacAskill has been to Ethiopia several years ago and had a close relationship with women who suffered the condition of obstetric fistula (an injury sustained after childbirth that causes a lack of control over defecating and urinating). The interesting part of this anecdote is that when faced with the possibility to donate to the Fistula Foundation (which provides medical care for women with that condition and other perineal tears), and a more effective foundation, MacAskill, firm in his beliefs, chose the latter.

Saunders-Hastings argues:

“Sometimes, welfare maximization will mean that recipients are paternalistically given less preferred benefits on the grounds of [effective altruists’] expectations that these will produce greater welfare returns. Elsewhere, it will mean that some people are denied benefits to which (on some moral views) they might plausibly have claims, on the grounds that resources can generate more good elsewhere. In both cases, what is at stake is the assumption of a donor’s entitlement to maximize on the pursuit of her own objective, without regard to other important ways of showing respect for beneficiaries and for the relationships that one finds oneself in.” 96

To summarize and link it to the anecdote: these Ethiopian women who were in the hospital of Addis Ababa showed MacAskill vulnerability and shared a part of their life. However, instead of showing reciprocity (by donating to the foundation that would have potentially helped them), he chose to give to a more effective foundation97. This may feel like a moral slight to these women and a failure to abide by his moral obligation to recognize other people as ends and not means (i.e., as people who deserve help regardless of whether that help could have been more effective or beneficial to someone else, not statistics or a ratio of people helped). Therefore, Saunders-Hastings views this as a failure of reciprocity because he prioritized a personal preference (effectiveness) over the moral obligation of reciprocity98.

Likewise, utilitarists99 ( who use the final result to decide whether an action is moral or not) could also criticize Saunders-Hastings for prioritizing a vague moral obligation of reciprocity over the possibility of making an efficient change. This conflict is based on the principles of consequentialism100 and its opposite: deontology (a moral philosophy that judges the action not on its predicted consequences but on its moral character (whether it’s right or wrong) using social norms and other rules)101.

3. Confusion and contradictions within the Effective Altruism community.

We have now seen two critiques of effective altruism that are not restricted to it but relevant to the application of utilitarianism’s principles in giving. However, specific critiques become harder to formulate as one grapples with the confusion and contradictions within the Effective Altruism community.

For instance, effective altruism lacks a unified position on key practices and principles.

As we’ve mentioned above, GiveWell102 (a meta-charity aligned with EA) supports cash transfers, while MacAskill (a proponent of EA and creator of the meta-charity Giving What We Can103 ) opposes them. Here, we see that there are different degrees of effectiveness to which meta-charities aligned with EA adhere.

Secondly, there seems to be different views on the place of political reform within this current. This raises the questions: Is effective altruism strictly about maximizing outcomes by directly intervening , or does it have the ambition of enacting political reform to indirectly improve the situation of the less fortunate ?

Peter Singer, an other figure of this movement, for instance, seems to support political reform:

“Political advocacy is an attractive option because it responds to critics who say that aid treats just the symptoms of global poverty, leaving its causes untouched.” 104 In the rest of this text extracted from his book, Singer promotes the foundation ONE. He defines it as an “advocacy-only organization co-founded by Bono, the lead singer of U2, focused on ending extreme poverty.”105

Singer also presents this foundation as being somewhat effective and in touch with the UN to better fund humanitarian organizations like the UN Consolidated Appeal for the Horn of Africa106. Similarly, institutions such as GiveWell seem to believe in the legitimacy of political reform. GiveWell107 (EA meta-charity) made a grant of $1.3 million to the Center for Pesticide Suicide Prevention in 2018108 . This center advocates for governments to ban the most lethal pesticides, and GiveWell supports it:

“One of our best guesses for where we might find significantly more cost-effective charities is in the area of policy advocacy, or programs that aim to influence government policy […] As a result, researching policy advocacy interventions is one of our biggest priorities for the year ahead.”109

On the other hand, other major EA institutions such as Giving What We Can110 and individual donors seem more attached to improving the lives of the poor internationally by allowing them access to better healthcare or simply relieving their financial situation (see majority of the testimonies in Singer’s book)111. Political reform remains, in their eyes, too uncertain.

However, what is troubling here is that despite Giving What We Can’s strong inclination for immediate, quantifiable effectiveness, this meta-charity still aims to achieve political reform. Based on the sentence “We aim to change the norms around charitable giving”112 on their front page, this message is fundamentally political. It presents Giving What We Can as an innovator in the field of philanthropy (which they are). Their mission requires a collective effort to enact long-lasting change, and implies a better redistribution of power; the same way policy reform does.

Moreover, Giving What We Can acknowledges and insists that its use of third-party evaluators does more than just inform donors; it helps pressure foundations to become more transparent and effective113.

In other words, GWWC isn’t just helping individuals make better choices, it’s actively reshaping the charity-landscape114. That’s a political intervention, whether they name it as such or not.

Ironically, this aligns them more with Rob Reich’s vision of reformist philanthropy (the kind that aims to make foundations more publicly accountable)115 than with the traditional effective altruist view that avoids engaging in systemic critique.

Thus, effective altruism has strong political ambitions even if it presents them implicitly, or tries to keep them on the margins of the movement. This contradiction is exacerbated by effective altruism’s aim for long-term change.

4. Contradictions in Longtermism

There are two avenues to longtermism: political reform and prevention of existential risks. In this section, I’ll show that the justification for prioritization of one over the other has an unstable basis.

Brian Berkey, a detractor of the institutional critique of effective altruism116 (whose main points are the ones underlined by Emma Saunders-Hastings117), argues that there’s a tension between the theoretical support for both existential risk prevention and political reform within Effective Altruism (EA) and its practical application: despite effective altruism’s need to be open to both areas to maintain its consistency, it prioritizes existential risk prevention over political reform118.

As a matter of fact, effective altruism allocates significant resources for AI prevention for the sake of future generations. Indeed, 11% of Giving What We Can donations were directed at that, while 0% went to political reform from 2020 to 2022119.

This could be explained by the following:

Effective altruism is an individualistic movement120, where donors focus primarily on their own actions, guided by the question “How can I have the most positive impact on the rest of the world, at my level?” without considering the broader collective efforts or the structural context in which they operate121. They tend to treat the world around them as a given, and shift their attention towards individual impact122.

Interestingly, Will MacAskill himself took EA to the political stage in 2022 during his speech at the UN123, signaling a rare effort by the movement to engage directly in political discussions. However, his framing of global issues still reflected EA’s individualistic roots, emphasizing the personal responsibility of individuals to maximize their impact, rather than calling for broader, systemic reforms that could address the root causes of global problems.

In this sense, preventing existential risks may appear as a task that someone simply ought to take on (because it’s concrete and morally urgent)124, whereas political reform, by contrast, is stagnant, collective, and heavily dependent on social context, which makes it less appealing to effective altruists125. This idea of a task one ought to undertake is echoed in Reich’s work, where he writes that foundations are meant to “supplement political institutions in fulfilling what John Rawls called the ‘just savings principle,’ especially as a hedge against remote, low-probability but highly consequential risks (such as potentially cataclysmic natural disasters)” 126.

In response to the funding of one future-oriented work (prevention of existential risk) over the other (political reform), Brian Berkey says that “This is simply an effect of effective altruists’ commitment to EA2 and EA3 [effectiveness and impartiality core principles]. Intuitively, however, this seems not only unobjectionable, but clearly appropriate.” 127

So he clearly justifies and defends this neglect of political reform by the search for traceable, quantifiable effectiveness.

However, the effectiveness-based justification Berkey gives is ultimately fallacious. Because it fails to account for the unsubstitutable qualities of political reform that may surpass its uncertainty, at least to allow it the same resources as the one dispensed for prevention of existential risk. Indeed, political reform and advocacy are the only cause areas that address the root of current problems128 (for example, lack of redistribution of wealth that leads to poverty, and animal abuse) that EA aims to solve or alleviate. Besides, simply investing in political reform (especially if successful) will allow us to pass down morals and social capital to future generations. To define this second point, we can refer back to Reich: “Here we understand social capital to refer to individual or collective attitudes of generalized trust, civicness, and reciprocity that are generated by and embedded in cooperative activities and networks.”129

The mistake Berkey makes is assuming that political theory should not be put into practice when the outcomes are hard to quantify130. It overlooks the fact that some of the most transformative social changes, like the advent of democracy, were initially unquantifiable and collective in nature131.

Besides, existential risk prevention may seem more tractable or concrete, especially in areas like AI safety (a cause strongly supported in effective altruism132), but its long-term consequences are speculative133. So, political reform should not be sidelined because its benefits don’t fit effective altruism’s narrow view of effectiveness. Rather, its intrinsic value and broad effects make it at least as worth supporting as risk prevention.

5. The FTX Scandal and the problem of psychology in Effective Altruism

Lastly, Effective Altruism claims to be the most rational and optimal form of giving134. Yet, it has, not long ago, proven vulnerable to one of the oldest failures in philanthropy: what Rob Reich calls the misuse of foundations “for the self-aggrandizement of donors “135. The best example of this is in what the EA community refers to as the “FTX crisis.” 136 In late 2022 and early 2023, the cryptocurrency exchange FTX, led by Sam Bankman-Fried, a prominent effective altruist, went bankrupt137 . The CEO, once praised for his philanthropic ambitions and his nonprofit FTX Foundation, was charged with fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering after it was revealed that over $8 billion in customer funds (FTX) had disappeared, to cover the losses of Almeda Research, FTX’s sister company138, which he also cofounded139.

While it would be unfair to equate all of Effective Altruism with Bankman-Fried’s actions, the attitudes and decisions of the movement’s leaders such as MacAskill’s response to credible warnings raise serious questions. This is where Yascha Mounk’s critique of the psychology of EA ( its tendency toward moral technocracy and self-rationalization)140 becomes strikingly relevant. Mounk warns that when individuals or elites believe they are acting for the common good, they may feel entitled to bypass ordinary norms of accountability, convinced that their superior insight justifies their morally questionable decisions141. This echoes Emma Saunders- Hastings’ critique of EA for its disregard for relationship ethics, with MacAskill again at the center142 .

Years before the collapse, between 2018 and 2019, multiple prominent EA figures, including Will MacAskill himself, received direct warnings about Bankman-Fried’s behavior143. These came not only from employees aligned with EA, but also from Tara MacAuley, co-founder of Alameda and former-chief of the Centre for Effective Altruism (CEA)144. She and others alerted MacAskill of “pervasive dishonesty, sloppy accounting, and rejection of corporate controls”145. As TIME MAGAZINE reported, these concerns “presaged the scandal that unfolded at FTX four years later.” 146 Despite this, MacAskill dismissed them as “rumors” and deepened his ties with Bankman-Fried, co-founding the FTX Future Fund with him in 2022, long after those initial warnings147.

This scandal exposes a deeper philosophical problem in EA’s logic, especially its “earning to give” mantra148. This mantra is mostly promoted by the 80,000 hours foundation149 which scouts ambitious, effective altruists, to guide them into their career choice, with the goal of obtaining a high salary, so they can donate more than the average person. We note that Bankman-Fried was MacASkill’s protegé and that he was encouraged by the 80,000 hours foundation to work in finance, rather than in animal welfare150. This foundation has already been criticized for condoning aggressively capitalistic attitudes, and devaluing necessary jobs like teachers, and nurses who do a lot of good, but not nearly as much as an investment banker giving away 10% of their salary151. So through this mantra, he justified his aggressive, high-risk financial behavior by claiming he would donate it all later to help future generations152. But, as Yascha Mounk observes, this logic allows people to excuse or condone almost any behavior under the guise of serving a greater good ( this is also one of the flaws of longtermism)153. The effective altruism community, in this case, failed to apply the caution and rationality it supposedly values154.

Here, the distinction drawn by Max Weber between the ethic of responsibility and the ethic of conviction becomes especially relevant155. EA claims to act out of rational responsibility, carefully weighing outcomes and consequences (the principles of an ethic of responsibility)156 . However, we see in this affair, a lack of prudence and a detachment from these rationality ideals, exemplified by MacAskill’s failure to even look into what he called “rumors’ about Bankman-Fried, to see if they were founded. This and his continued support of Bankman-Fried from 2018 to 2022 reveals a dangerous drift into moral conviction, the belief that as long as one’s intentions are good ( helping the long-term future), the means are justified157. But, as Weber warns158, and as the saying goes: hell is paved with good intentions.

The irony is palpable: MacAskill himself wrote in What We Owe the Future: “History is littered with people doing bad things while believing they were doing good. We should do our utmost to avoid being one of them.”159 Yet, he ignored warnings, trusted a man with suspicious wealth, and then claimed to be shocked when the deception collapsed. His later tweet: “I had put my trust in Sam, and if he lied and misused customer funds he betrayed me, just as he betrayed his customers, his employees, his investors, & the communities he was a part of.” 160 seems empty at best, hypocritical at worst. If the leaders of a movement act this way, it calls into question the reliability and integrity of the movement itself161.

Even Tara MacAuley, former leader of the CEA (Center for Effective Altruism), has since distanced herself from the community162 . Thereby, the « earning to give » logic, once hailed as revolutionary, is left looking naive and dangerously enabling.

III. Synthesis (refocus on giving what we can (GWWC)

- What it does well

Overall, Giving What We Can remains a model for meta-charities and a moderator for foundations in general, since it aims to correct many common flaws of the charity landscape163. As we’ve seen, it promotes transparency and measurable impact through both the use of third-party evaluators to create the rankings164, and the availability of almost yearly reports165 that illustrate the allocation of donations to different causes (human welfare, animal welfare, and longterm risk prevention) and to different foundations, like the Malaria fund166 ). Giving What We Can also features reports on specific charities like the Against Malaria Fundation167.

Giving What We Can’s political mission of encouraging foundations to be more effective in order to receive more donations is also an added value168. Here, the strategic nature of their endeavor helps reform philanthropic giving, even if the meta-charity remains reluctant to support political reform directly. Finally, the pledge to give a minimum of 10% of one’s salary169 to charities is an innovative way to encourage well-meaning people to move from one-time, emotional giving to a more regular and thus more effective form of giving170. These strengths, while straightforward in form, have had a profound effect on how individuals engage with giving and have led to a sizable improvement in the charity-landscape171. The simplicity and moral value of the concept “better giving by researching the best charities for you” is so commendable that, to criticize Giving What We Can, one must carefully contextualize its limitations.

- The limits of Giving What We Can

We’ve shown that Giving What We Can has the power to channel donations into main causes (human welfare, animal welfare, existential risk), but it excludes political reform (0% of recommended funding)172.

Despite its claims to change donation norms, it still channels donors toward a narrow vision of effectiveness that erases political reform from the causes to support173. Oddly enough, this point is completely understood by other major meta-charities aligned with effective altruism, albeit less focused on recommendations and more on research. GiveWell174 states on their website that “Our intuition is that spending a relatively small amount of money on advocacy could lead to policy changes resulting in long-run benefits for many people, and thus could be among the most cost-effective ways to help people.”175 .This shows that Giving What We Can underestimates the importance of political reform to address systemic injustice.

While philosophically the movement includes a diversity of thought (Singer supports systemic change176, and GiveWell acknowledges the potential of advocacy and as mentioned previously, supports through grants entities that pressure governments to start political reform (e.g. GiveWell made a grant of $1.3 million to the Center for Pesticide Suicide Prevention in 2018, which advocates for governments to ban the most lethal pesticides177), in practice effective altruists only act within the current structure of the world, taking the world as a given and not trying to change its institutions178, which, ironically, would be the most effective way to address the pressing issues they’re preoccupied with179 .

Finally, we should note that unlike historical foundations, it avoids supporting innovative public goods or policy reform. So, Giving What We Can hinders itself from being an agent of social discovery,

To better explain what it means for a foundation to be an agent of social discovery180 , we can refer to Rob Reich , who affirms that one of the key advantages of philanthropic giving, is oddly enough: the perpetuity that characterizes foundations (including meta-charities)181.

He formulates this argument in opposition to his explanation of Mill and Turgot’s reservations towards the perpetuity of the foundations: “To permit foundations to exist in perpetuity amounts to making “the dead, judges of the exigencies of the living” and that “under the guise of fulfilling a bequest” a foundation transforms a “dead man’s intentions for a single day” into a “rule for subsequent centuries182. While acknowledging these disadvantages, and dangers, he still sees some merit in the idea of perpetual entities, especially through their ability to foster social discovery183 :

Unlike the state, which is subject to the pressure of electoral mandates and the constant need to respond to the short-term demands of voters, foundations are free from immediate political pressures184. This means they can afford to focus on long-term challenges (like climate change or artificial intelligence risk if they wish to) that the government often neglects in favor of more urgent, but less transformative 185, problems like unemployment or poverty.

This long-term perspective, combined with substantial resources, enables foundations to undertake experiments that the state cannot. Rob Reich gives the example of the Carnegie Foundations186, which mostly funded the first public libraries in the United States. Their success and public value eventually led to the maintenance of public libraries fully becoming a responsibility of the state187. Thus, the project of a foundation became a permanent policy to the benefit of everyone. In this way, philanthropic foundations can lay the groundwork for future public policy.

Hence, in the case of Giving What We Can, their narrow view of what is effective doesn’t allow this meta-charity to embrace the full democratic role of foundations.

One might argue that there are other meta-charities that try to take on the role of innovators. However, while it is true that other meta-charities like GiveWell188 explore systemic change through research and policy advocacy, this does not excuse Giving What We Can’s omission of it. As one of the most visible and norm-setting actors in effective altruism189, its narrow framing of what counts as “effective” reinforces the political detachment within the movement.

Conclusion:

Effective Altruism offers a set of practices for increasing the impact of donations, whether aimed at human or animal welfare. Its emphasis on transparency allows donors to trace the effectiveness of their contributions, and organizations like Giving What We Can demonstrate a strong commitment to transparency by openly acknowledging past mistakes. However, when applied internationally, especially in the Global South for human welfare or healthcare purposes, Effective Altruism risks replicating the paternalism long associated with traditional philanthropy. Moreover, its core assumption that effectiveness is the ultimate measure of good is not universally accepted. As such, some thinkers like Saunders-Hastings argue that this view may lead effective altruists to neglect their moral obligations, and relational ethics.

The movement’s internal inconsistencies further complicate critique. Its partial embrace of longtermism raises an inconsistency between the neglect of political reform and the place of existential risk prevention. We’ve gathered that if we accept the legitimacy of preventing long-term risks on the basis of it being low probability, but high reward and quantifiable, then political reform deserves at least equal consideration, and support, because it’s high reward and a source of social capital.

To illustrate these reflections, we turned to Giving What We Can. This organization represents the practical aspect of the ideological movement that is effective altruism, that is more binary (more focused on outcomes) than the ideological current. We’ve found that no political reform oriented foundations were recommended. So while the organization brings relief to the current struggles of the less fortunate, it often takes the current political world as a given. Despite its unambiguously political mission of changing norms in the philanthropic sector, it rarely advocates for systemic change. An example of this tendency is the “earn to give” mentality, that meta-charities like 80,000 Hours promote. This approach has been criticized for encouraging aggressive, capitalistic career paths in order to maximize donations for the common good.

We can then make a suggestion for change: as the platform that channels the most donors into specific cause areas, Giving What We Can should recommend donations to organizations that work toward political reform. Doing so, could help fulfill what Rob Reich identifies as an essential function of philanthropy: to serve not just present needs, but also the innovation of society for future generations. The example of Rutger Bregman190 who donates 10% of his income in the spirit of Effective Altruism while promoting radical reforms like universal basic income and open borders in Utopia for Realists shows that these two commitments are not mutually exclusive, but complete each other.

© Rim Benrhazi, 2025

Endnotes:

1 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 7.

2 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 9.

3 Ibid.

4 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 8.

5 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 4.

6 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 9-10.

7 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 2.

8 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 5.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 6.

12 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 7.

13 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 139.

14 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 25.

15 Amber Dawn, Pablo, MichealA, Aaron Gertler, “History of effective altruism”, Forum Effective altruism, 2025(since2020) Link

16 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 78.

17 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 77.

18 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 78

19 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 8.

20 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 78-79

21 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 75 and 83.

22 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 84.

23 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 82.

24 Ibid

25 Ibid

26 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 122.

27 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018),150.

28 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 144.

29 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018),145.

30 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018),146.

31 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 49.

32 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 54.

33 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018),51.

34 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 50.

35 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 48.

36 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 157.

37 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 158-159.

38 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 156-157, fig 4.2.

39 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 129.

40 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 197.

41 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 6.

42 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 18.

43 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009.Link

44 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Recommendations, Best charities, Against malaria Foundation. Link

45 Registered 501 ©(3) in the Uk, project of the Centre for Effective Altruism, 2017. Link

46 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009.Link

47 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 58-59.

48 Henry R.West, Brian Duigman, “utilitarianism” Britannica, 2025. Link

49 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 9.

50 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 118 -120.

51 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 85-88.

52 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 87, fig 2.7.

53 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 120.

54 Ibid.

55 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Donate, Where we focus to have the biggest impact Link

56 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, More Impact with Funds Link

57 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, All Causes Bundle Link

58 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, 2020–2022 Impact evaluation (working sheet) Google sheets

59 Ibid

60 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 81-82.

61Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 29.

62 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, How rich am I ? Link

63 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, the 10% pledge Link

64 Ibid.

65 Ibid.

66 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Donate, Where we focus to have the biggest impact Link

67 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Research: Our research and approach Link

68 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Research: Evaluating Evaluators Link

69 Ibid.

70 Ibid.

71 Ibid.

72 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, About us: Our mistakes Link

73 Ibid.

74 Ibid.

75 Ibid.

76 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 93.

77 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 16.

78 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 147.

79 GiveDirectly, 2009, Link

80 GiveDirectly, 2009, About: our work: What do we do?Link

81 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 149.

82 GiveWell,2007 Link

83 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009.Link

84 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 144.

85 There’s been however active pushing to listen to the poor: Voices of the poor; can anyone hear us?( English), World Bank Group, 2000, Link

86 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 143-163

87 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 149.

88 Ibid.

89 Ibid.

90 Ibid.

91 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 150.

92 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 147.

93 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 150.

94 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 151.

95 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 150-152

96 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 150.

97 Ibid.

98 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 151.

99 Henry R.West, Brian Duigman, “utilitarianism” Britannica, 2025. Link

100 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, ethics of care, consequentialism,Britannica, 2025. Link

101 The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica, ethics of care, deontological ,Britannica, 2025. Link

102 GiveWell,2007 Link

103 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009.Link

104 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 161

105 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 162

106 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 161

107 GiveWell,2007 Link

108 The GiveWell Blog, Considering policy advocacy organizations: Why GiveWell made a grant to the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention,2018 Link

109 Ibid.

110 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009.Link

111 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 7.

112 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, PLEDGE to give what you can Link

113 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Research: Our research and approach Link

114 Ibid.

115 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 166.

116 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 3.

117 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 150.

118 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 22.

119 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, 2020–2022 Impact evaluation (working sheet) Google sheets

120 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 5

121 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 8.

122 Ibid.

123 UN dispatch, How “Longtermism” is Shaping Foreign Policy | Will MacAskill, Mark Leon Goldenberg, 2022 Link

124 William MacAskill, Longtermism, William Macaskill, 2022, Link

125 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 14

126 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 23

127 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 19.

128 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 150.

129 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 178

130 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 19.

131 Jan-Erik Refle Measuring democracy among ordinary citizens—Challenges to studying democratic ideals,Frontiers, 2022 Link

132 See, GWWC’s page, or William MacAskill, Longtermism, William Macaskill, 2022, Link

133 Ami Srinivasan, Stop the robot apocalypse, London Review of Books 37, 2015, 3-6

134 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 4

135 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018),49

136 Amber Dawn, Pablo, MichealA, Aaron Gertler, “FTX crisis ”, Forum Effective altruism, 2025(since2020) Link

137 Ibid.

138 Amber Dawn, Pablo, MichealA, Aaron Gertler, “FTX collapse ”, Forum Effective altruism, 2022 Link

139 Ibid.

140 Yascha Mounk, The Problem with effective altruism, Persuasion, 2024 Link

141 Ibid.

142 Emma Saunders-Hastings, Private Virtues, Public Vices: Philanthropy And Democratic Equality (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 152.

143 Charlotte Alter Exclusive: Effective Altruist Leaders Were Repeatedly Warned About Sam Bankman-Fried Years Before FTX Collapsed, 2023 Link

144 Ibid.

145 Ibid.

146 Ibid.

147 Ibid.

148 Yascha Mounk, The Problem with effective altruism, Persuasion, 2024 Link

149 Benjamin Todd, William MacAskill, 80,000 hours,2011 Link

150 Charlotte Alter Exclusive: Effective Altruist Leaders Were Repeatedly Warned About Sam Bankman-Fried Years Before FTX Collapsed, 2023 Link

151 Yascha Mounk, The Problem with effective altruism, Persuasion, 2024 Link

152 Ibid.

153 Yascha Mounk, The Problem with effective altruism, Persuasion, 2024 Link

154 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 5

155 Sung Ho Kim, Max Weber, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2022 Link

156 Ibid.

157 Charlotte Alter Exclusive: Effective Altruist Leaders Were Repeatedly Warned About Sam Bankman-Fried Years Before FTX Collapsed, 2023 Link

158 Sung Ho Kim, Max Weber, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2022 Link

159 William Macskill, What We Owe The Future, ( Basic Books New York, 2022), 254

160 Charlotte Alter Exclusive: Effective Altruist Leaders Were Repeatedly Warned About Sam Bankman-Fried Years Before FTX Collapsed, 2023 Link

161 Yascha Mounk, The Problem with effective altruism, Persuasion, 2024 Link

162 Charlotte Alter Exclusive: Effective Altruist Leaders Were Repeatedly Warned About Sam Bankman-Fried Years Before FTX Collapsed, 2023 Link

163 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 5

164 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Research: Our research and approach Link

165 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, 2020–2022 Impact evaluation (working sheet) Google sheets

166 Ibid.

167 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Against malaria foundations: Bednets to prevent malaria Link

168 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, Research: Our research and approach Link

169 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, the 10% pledge Link

170 Peter Singer, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 5

171 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, What are the best charities to support in 2025? Link

172 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, 2020–2022 Impact evaluation (working sheet) Google sheets

173 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009, What are the best charities to support in 2025? Link

174 GiveWell,2007 Link

175 The GiveWell Blog, Considering policy advocacy organizations: Why GiveWell made a grant to the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention,2018 Link

176 Endorsement of ONE foundation and Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative in Peter Singer’s, The Most Good You Can do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically, (Yale University, 2015), 161-162

177 The GiveWell Blog, Considering policy advocacy organizations: Why GiveWell made a grant to the Centre for Pesticide Suicide Prevention,2018 Link

178 Brian Berkey, The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism, ( Forthcoming in Utilitas, University of Pennsylvania, 2017) 8.

179 Lisa Herzog, (One of) Effective Altruism’s blind spot(s), or: why moral theory needs institutional theory, Justice Everywhere, 2015 Link

180 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 191

181 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 8

182 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 54

183 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 191

184 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 159-193

185 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 161

186 Rob Reich, Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy, (Princeton University Press, 2018), 164

187 Ibid.

188 GiveWell,2007 Link

189 Toby Ord, William MacAskill, Giving What We Can 2009.Link

190 Rutger Bregman, Utopia For Realists,( Little Brown and Company, 2017)

Laisser un commentaire